A couple of years ago, out of the blue, Ysbrand Brouwers of the ANF (Artists for Nature Foundation) called and asked me whether I would be interested in an all-expenses-paid trip to Alaska in May 2025, to paint the wildlife and landscape of the Copper River Delta – one of the most diverse and untouched marine and wetland ecosystems in the world. It wasn’t a difficult decision to make, and that initial conversation resulted in two separate trips to Cordova, Alaska, in May 2025 and then January 2026. (image below, photo credit: M G Whittingham)

‘The Heartbeat and Lifeblood of an Alaskan Rainforest’ is the official name of the project, a collaboration between the ANF, headed by Ysbrand Brouwers, and the Native Conservancy (NC), headed by Dune Lankard, an Eyak elder. The project is built on the success of an earlier ANF collaboration with Dune in 1998 (with participation from many SWLA artists).

As Dune and other project support staff explained soon after we touched down in Cordova, the natural resources of the Copper River and Prince William Sound area have been (over-) exploited for hundreds of years: sea otter fur traders from Russia, gold prospectors from the US, the development of salmon and oyster fisheries, industrial copper mines and industrial oil extraction. Add to this the great Alaskan earthquake of 1964, and the Exxon Valdez oil disaster in 1989, and it is easy to imagine how these fragile ecosystems have been under severe pressure.

Likewise, the native communities have struggled to maintain their way of life. The Eyak were the original inhabitants of the Cordova region, sandwiched between the Chugach and Tlingit peoples, and they struggled to adapt to the changes the 20th century brought to the region, losing their last speaker in 2015. Nevertheless, the remaining Eyak still maintain a cultural polity, together with an awareness of the importance of an ecologically sustainable lifestyle, based around subsistence hunting, the harvesting of wild salmon and, latterly, kelp farming.

Dune explained how the 1998 project book had been an invaluable tool of environmental advocacy for the NC in their efforts to ‘protect ancestral land, revive ocean abundance, and support thriving Indigenous communities’. But now, according to Dune, the region was facing a whole new raft of environmental challenges and threats, and it was time for a new project, with new eyes and fresh interpretations. Ysbrand and ANF VP Bruce Pearson visited Cordova in 2024 and finalised the collaboration with the NC: this new project would take the form of four separate artists’ residencies, and result in a book, a travelling exhibition, and a short documentary film. The project would aim to ‘provide an inspirational portrait of the biodiversity and historical significance of the region…and build political/cultural consensus to repatriate Indigenous ancestral lands…’

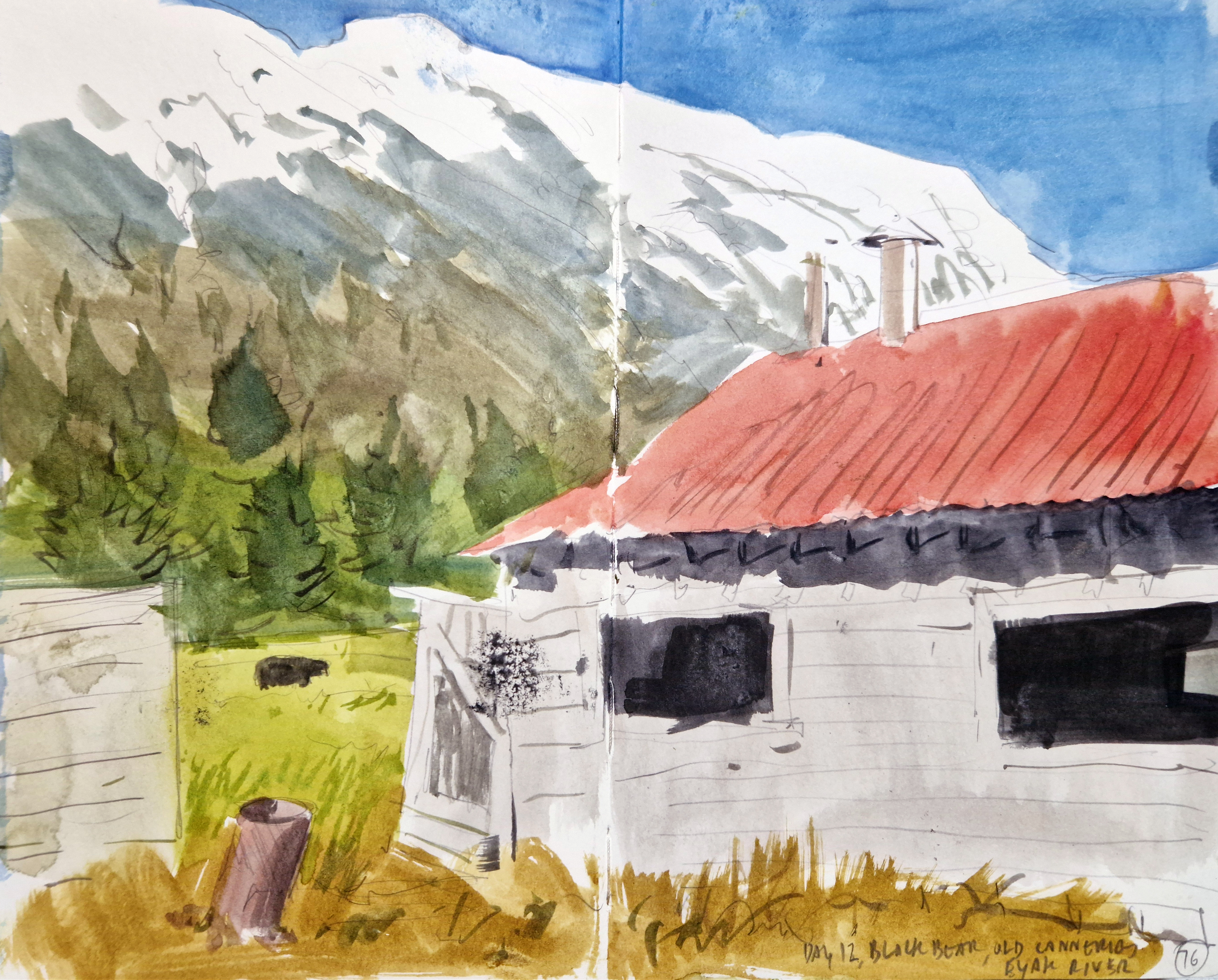

So here I was in May 2025, with Andrea Rich (SWLA), Kokay Szabolcs (SWLA), and Laurent Willenegger, listening to Dune’s inspirational speech. We were guests of the Native Conservancy at Eyak Lodge, on the shores of Eyak Lake, surrounded by snow-capped mountains, with the yikkering calls of bald eagles echoing off the forested valleys. There was a whole team supporting us: Robert Massolini, our gun-wielding guide, drove us around to some amazing locations and kept us safe from hungry bears. Yoshi in the lodge kept us incredibly well fed, and Dune, April, and David Grimes kept us entertained and informed, with their anecdotes, stories, and tales of environmental activism.

For us artists, all we had to do was…paint. What a dream, to be fed and watered, and then ferried around to some of the most stunning places I have ever seen! We visited iceberg-filled glacial lakes, moss-covered muskeg forests, and swampy riverine wetlands. We took a tiny aircraft over a glacier, a boat down the river to the delta, and paddled kayaks between tiny, deserted islands. We saw bears, moose, mountain goats, and all sorts of birds.

There were challenges, of course. The Copper River Delta region is wet. Very, very wet. The region is defined by precipitation in one form or another: constant rain and snow throughout the year, with streams, rivers, and glaciers cutting myriad trails through the landscape, and carrying silt, minerals, and nutrients into the ocean. For the whole of the first week, we awoke to the sound of driving rain, and struggled to produce work, huddled beneath tarps. But we were out every day, dawn to dusk, and our spirits were never dampened. For the second week the rain eased a little, we enjoyed several days of glorious sun. As ever it was inspirational to watch and learn from my fellow artists – we were a remarkably diverse group with different ways of tackling the landscape and wildlife, which only made it even more interesting for me.

In August 2025, a second residency took place, with Barry Van Dusen (SWLA), Siemen Dykstra, Paschalis Dougalis, and Roseanne Guille. Despite the rain – and mosquitoes – this group produced amazing work, concentrating particularly on the salmon runs, Sea Otter Island, and Childs Glacier.

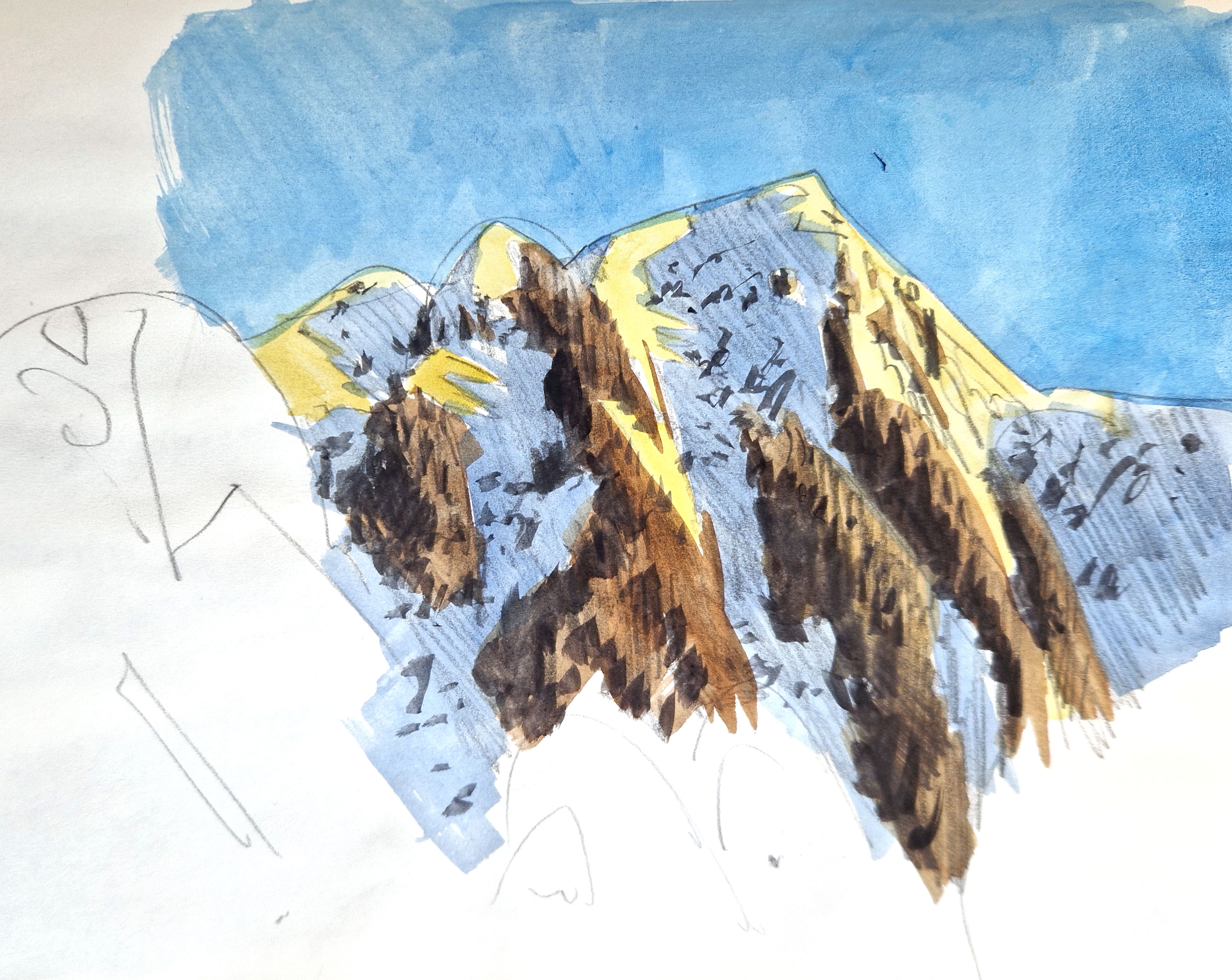

It wasn’t until I was home again, that Ysbrand invited Laurent Willenegger and me back to Cordova for the January 2026 residency. How could I resist? This time it would be a little different: just us two artists (and Laurent’s son Jolan, who would be recording footage) staying at local artist Denis Keogh’s house. Arriving at Cordova’s tiny airport in minus 25 degrees Celsius, we were met by Denis and our guide Robert, and whisked off straight away to the winter wonderland of Sheridan Lake – frozen solid and filled with giant turquoise-blue bergs, with the glacier snow-capped peaks as a backdrop.

We settled quickly into our working routine. Starting the day with a hearty cooked breakfast, we packed our gear, put on our multitude of layers, and headed out for the entire day: painting and looking for wildlife. Back at nightfall, more fantastic grub, then straight to bed for a well-earned rest. The weather was, of course, challenging: I had constructed a painting box with a built-in warming pad in order to keep my paints and brushes from freezing, but quickly found out that under -15 degrees, the paper itself froze solid, making any sort of work nigh impossible. For several days, it hovered around minus 5, and I was able to work with, and indeed encourage, the freezing and crystallisation of the paint within the surface of the paper.

Laurent mixed in vodka to keep his paints from freezing, though he struggled too with the more extreme temperatures. I was really glad to have the company of someone who loved painting outside as much as I do, and I appreciated his expert tracking and observation skills – honed in the mountains of his native Switzerland. Jolan’s footage was also a revelation: like a third eye, his drone soared over the landscape and approached the moose and mountain goats that we saw only as distant shapes through our telescopes.

For several days the temperature reached 4 degrees Celsius, and it rained. We hid under bridges and painted the frozen wilderness. It was difficult to see wildlife, but every encounter was so much more intense because of that. We saw distant moose drifting through the brush, and the last of the year’s silver salmon gathered in the streams: blind ‘zombie fish’ waiting to be picked off by eagles, otters, or coyotes. We sketched some bald eagles fighting over the remains of a duck by the side of a river: one young eagle was gravely injured and didn’t make it. The winter in Alaska is savage, and survival is balanced on a knife-edge.

My time by the Copper River Delta in Alaska has left me with a rather paradoxical impression. On the one hand, I felt touched by the raw wildness of it all: the vast open spaces, soaring mountains, and untouched wilderness: I had the wonderful feeling of being a spectator, witnessing the wildlife just getting on with their savage and beautiful lives. On the other hand, however, I felt somehow closer to man’s destructive forces: faced with the reality of the retreating glaciers, the ongoing threat of forestry, mining and oil extraction, the constant Trump-tainted conversations with our hosts. Everything is big in Alaksa: big wilderness, with correspondingly big problems. My little Danish island suddenly felt small and inconsequential.

Stopping in Anchorage on our way home, we took a trip downtown and visited the fantastic (and well-funded) museum filled with incredible ethnographica and art. Outside, in the freezing ice-covered city, groups of homeless Native Alaskans listlessly paced the streets back and forth, some drunk or high, and literally keeling over before us – and I couldn’t help but be reminded of the condemned silver salmon I had seen gathering in the eddies of Power Creek just a few days previously. Again, I was keenly aware of how superficial my visit had been, and how I had only begun to scratch the surface of the enormously complicated cultural, political, and environmental reality of 21st-century Alaska.

Most of all, however, when I think back to my two residencies in Cordova, I think of the great people I met and shared time with, and the incredible generosity of Dune, April and the Native Conservancy, as well as all the support of the local people. I can’t wait to see what the artists on the fourth residency come up with, and how the book, exhibition and/or film might turn out. Every time I felt despondent about the state of affairs, something would happen or someone say something to give me hope – thank you Cordova!

ps – if you’ve made it this far, you may be interested in looking at some more images from the residencies here